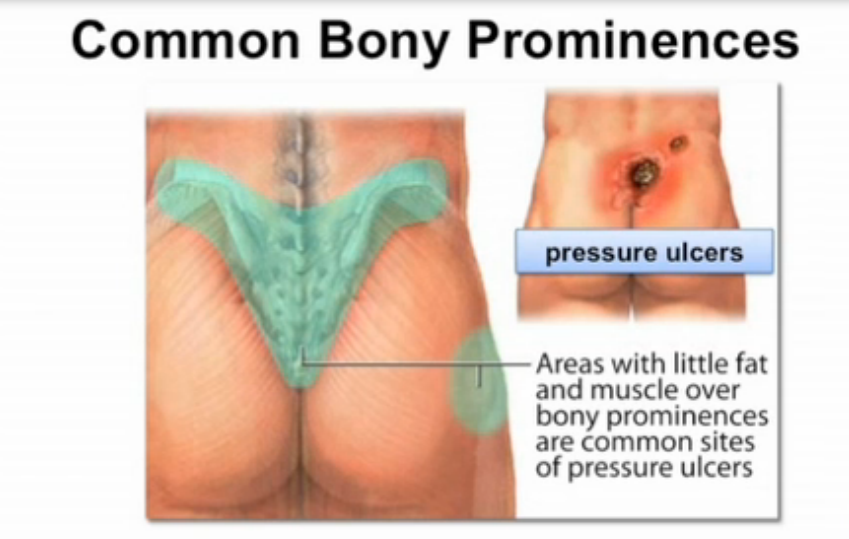

A pressure injury is localized damage to the skin and underlying soft tissue usually over a bony prominence or related to a medical or other device. The injury can present as intact skin or an open ulcer and may be painful. The injury occurs as a result of intense and/or prolonged pressure or pressure in combination with shear.

Pressure injuries occur in up to 23% of patients in long-term and rehabilitation facilities and at an incidence of 10% to 41% in ICU patients. In a report by reported nearly 2.5 million individuals are affected by these injuries, with a mortality of more than 60 000 patients in the US each year.

The incidence of pressure ulcers is increasing due to an aging population with decreased mobility and increases in morbidity associated with obesity and cardiovascular disease. Each year, more than 2.5 million people in the United States develop pressure ulcers. Up to 28 percent of nursing home residents have pressure ulcers. Special wound care is needed in 35 percent of nursing home residents with stage 2 or higher pressure ulcers. Once developed, pressure ulcers typically need a lengthy course of treatment, with an annual cost in the United States near $11 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project for adult

hospital stays in 2006.

The mortality rate in patients with a pressure ulcer was significantly higher than in patients without a pressure ulcer (9.1% versus 1.8%, OR = 5.08, CI: 5.03-5.1, P <0.001). Pressure ulcers were significantly more common in patients who were older or had malnutrition. The results of this study confirm the importance of prevention initiatives to help reduce the negative impact of pressure ulcers on patient outcomes and costs of care.

(Pressure Ulcers in the United States’ Inpatient Population From 2008 to 2012: Results of a Retrospective Nationwide Study, Bauer et al. Wound Management & Prevention, 2016;62(11):30-38.)

Chronic wounds characteristics:

Major contributing factors (alone or in combination):

DIAGNOSIS

Evaluation of the patient’s skin for signs of a pressure injury is vital. Pressure injuries are notoriously recurrent and difficult to treat. Any patient with mobility issues is at risk for development of an ulcer.

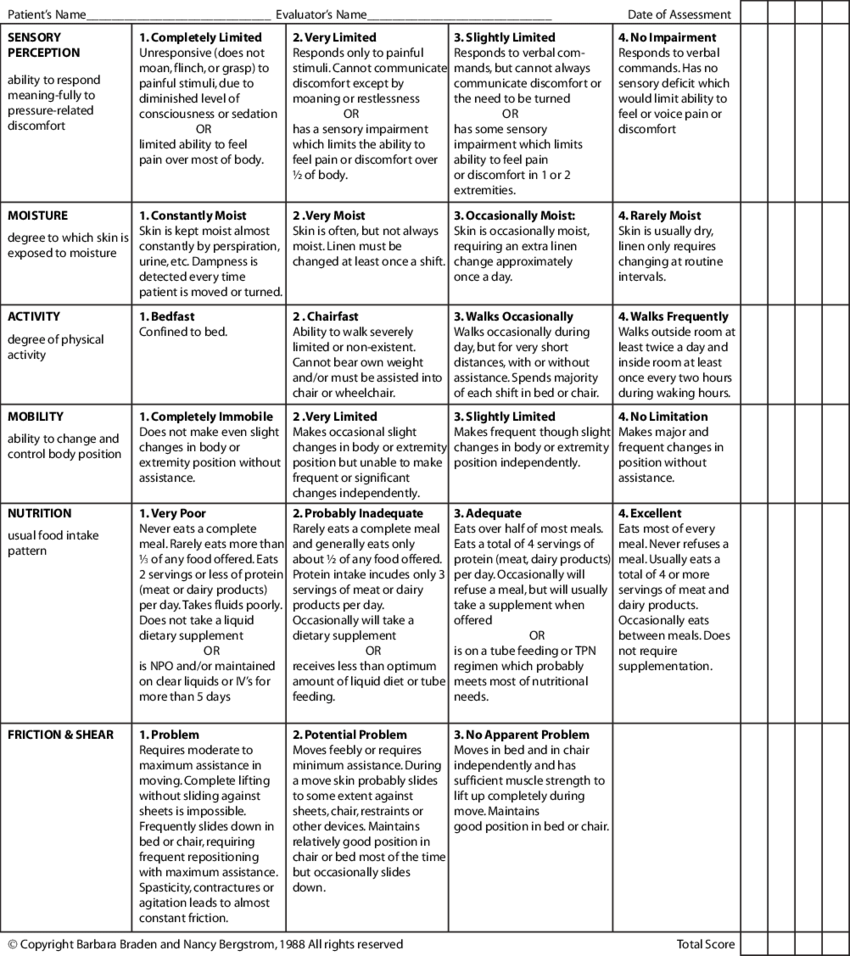

Routine daily assessment for at-risk patients therefore usually includes a Braden scale evaluation:

The risk of an immobile patient with other co-morbidities increases rapidly from a high-normal of >20 to a low (<15) score, improving as the condition improves.

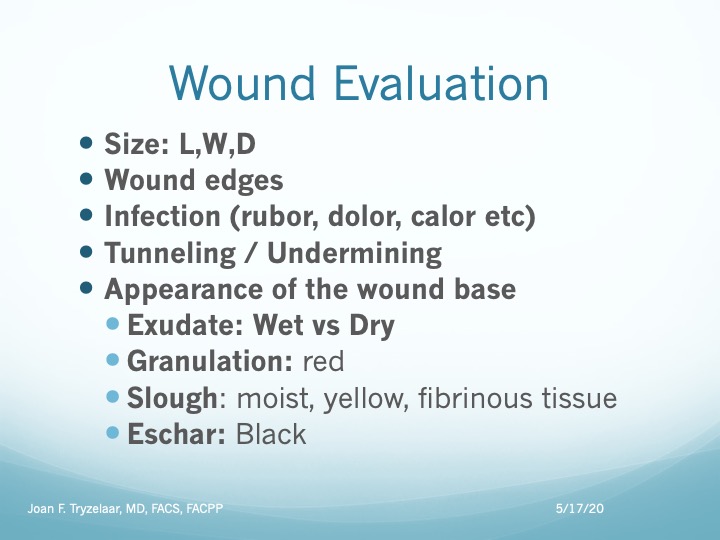

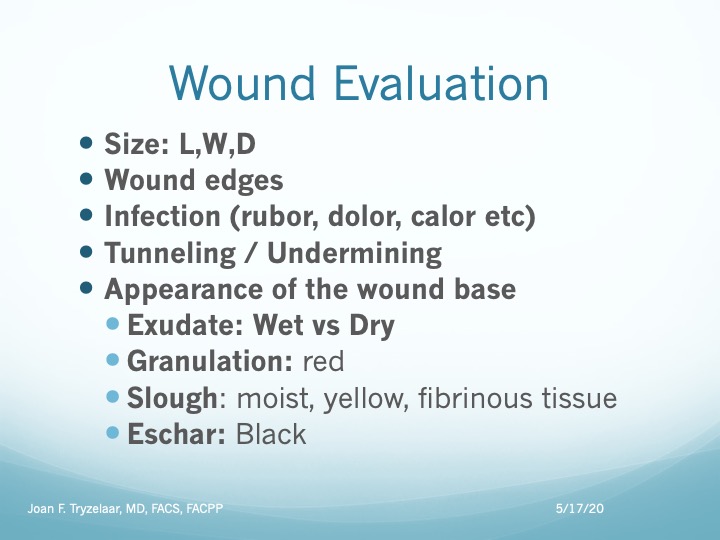

Wound Assessment:

- Type (alone or in combination):

- Pressure

- Venous stasis

- Diabetic

- Ischemic

- Atypical

- Size (Length x Width x Depth)

- Undermining

- “Rolled” edges (Epibole)

- Wound tissue type and amount

- Slough

- Granulation

- Exudate type and amount

- Peri wound appearance

- Cellulitis

- Epitheliazation

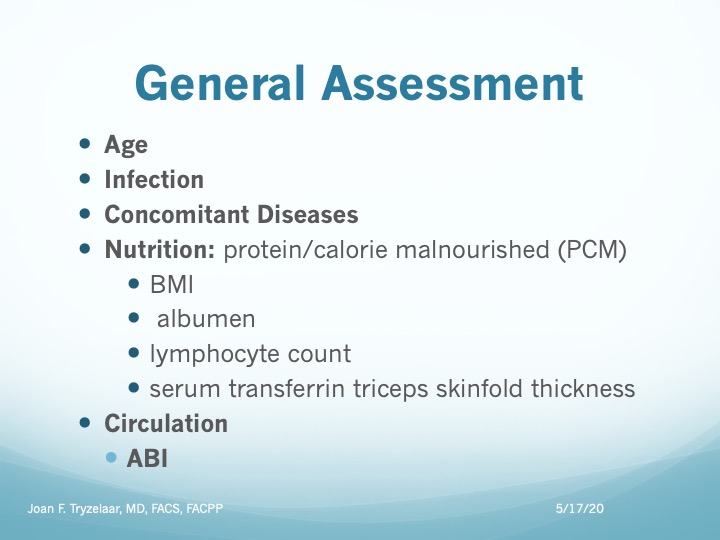

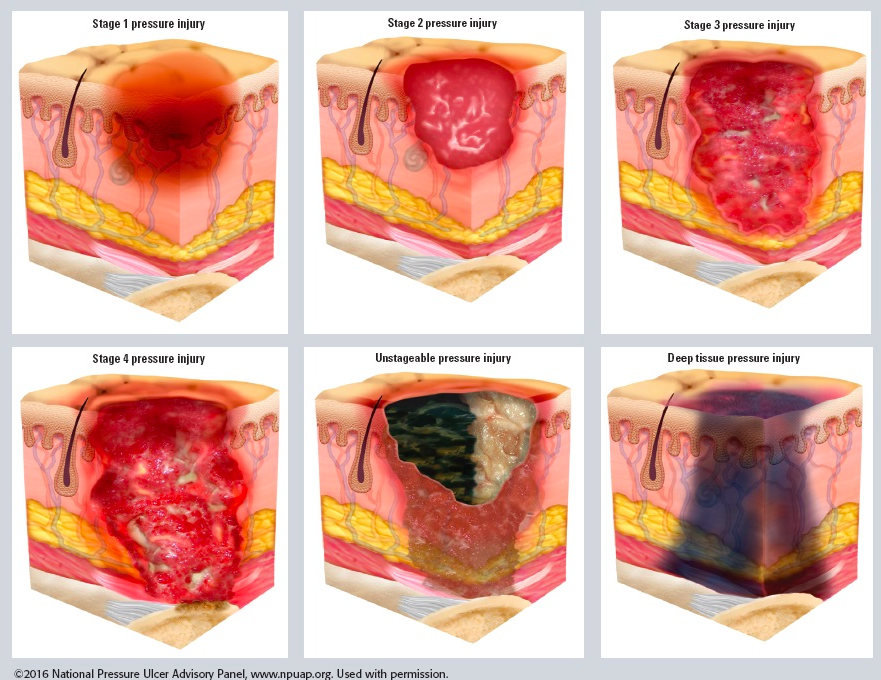

Any evaluation of a pressure injury includes assigning a stage to the wound. Staging helps determine what treatment is best for you. You might need blood tests to assess your general health.

STAGES

- Stage 1 Pressure Injury: Non-blanchable erythema of intact skin.

- Stage 2 Pressure Injury: Partial-thickness skin loss with exposed dermis

- Stage 3 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin loss

- Stage 4 Pressure Injury: Full-thickness skin and underlying tissue loss (muscle, bone).

- Unstageable Pressure Injury: Obscured full-thickness skin and tissue loss

- Deep Tissue Pressure Injury: Persistent non-blanchable deep red, maroon or purple discoloration.

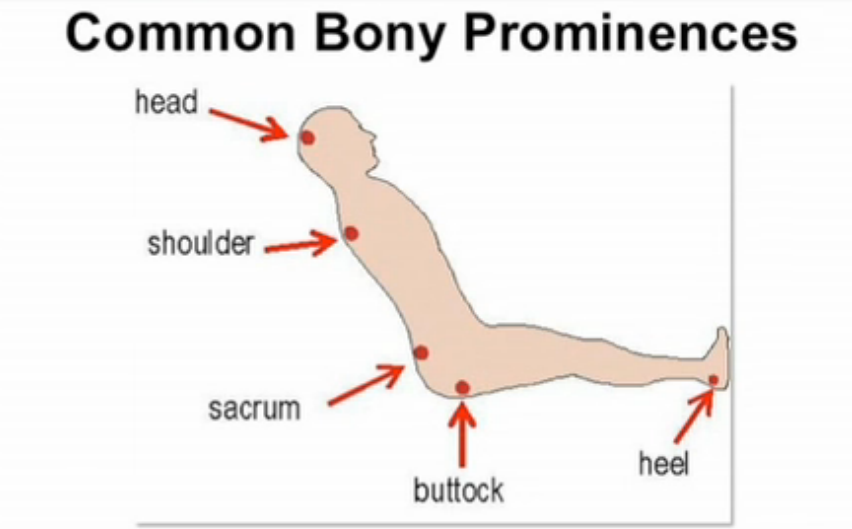

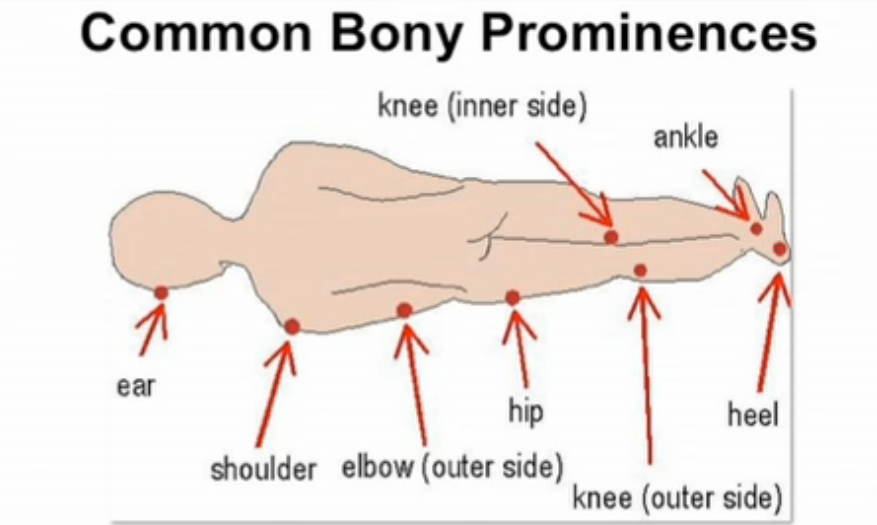

COMMON LOCATIONS

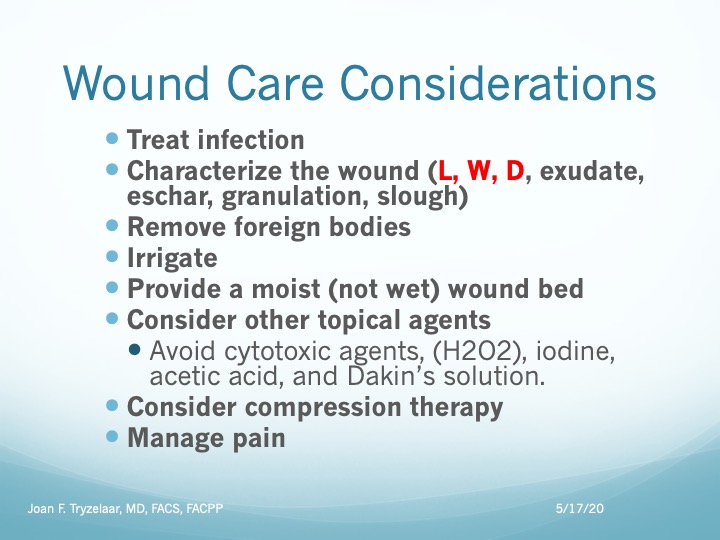

GENERAL CARE

- Reduce or eliminate underlying contributing factors by providing pressure redistribution with proper positioning and support surfaces.

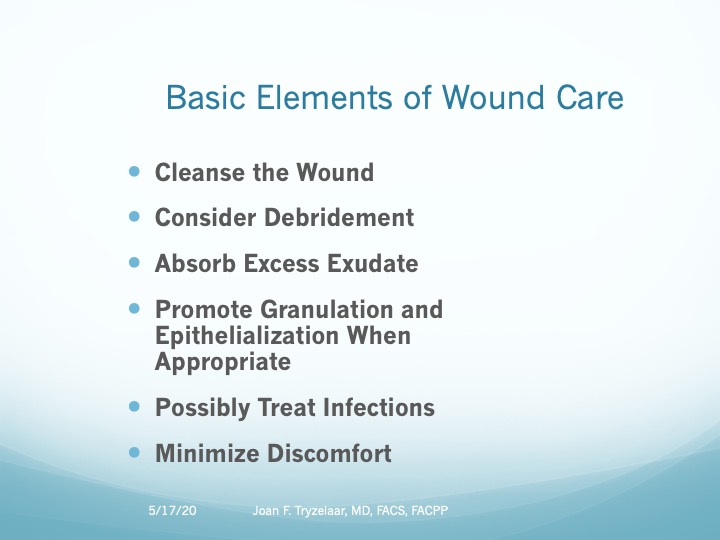

- Provide appropriate local wound care, which may include debridement for patients with necrotic tissue, based on the ulcer’s characteristics.

- Control pain. Local factors that may be contributing to pain such as ischemia, infection, or breakdown of the surrounding skin should be addressed. Initial and ongoing pain assessment should be documented using a pain scale.

- Treat infection — All open ulcers are colonized with bacteria, but only clinically evident infections should be addressed with culture and antibiotic treatment. Patients with deep wounds should be evaluated for the presence of osteomyelitis.

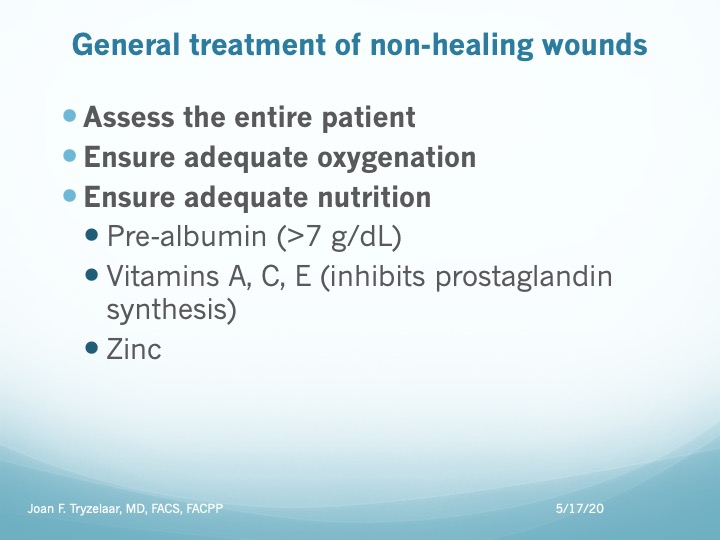

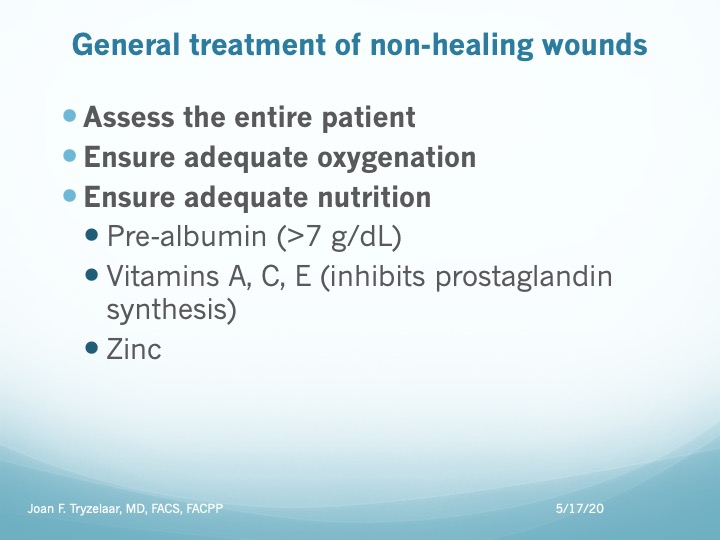

- Optimize nutrition — Patients with pressure-induced skin and soft tissue injuries are in a chronic catabolic state. Optimizing both protein and total caloric intake is important, particularly for patients with stage 3 and 4 pressure injuries.

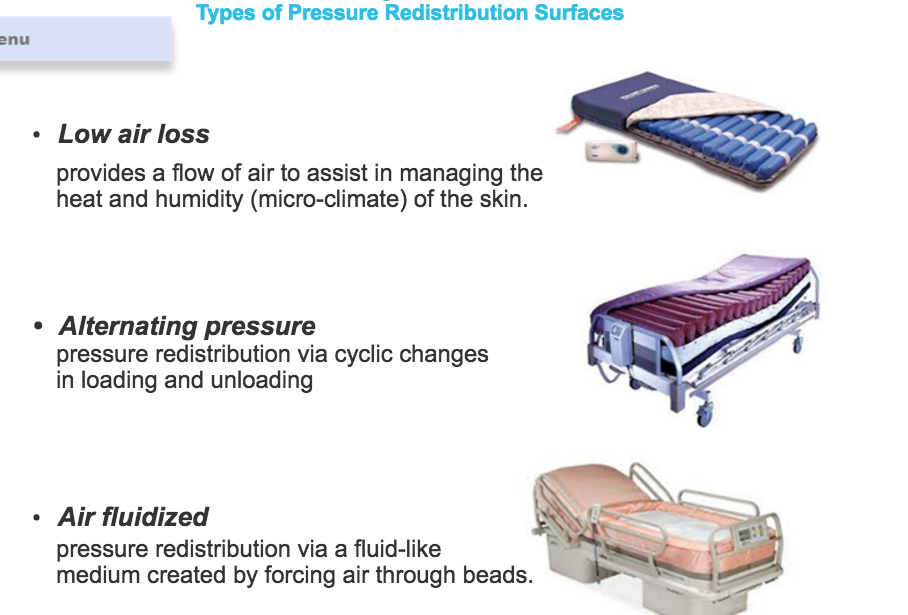

- Redistribute pressure — Proper positioning and support to minimize tissue pressure should be provided for all patients, particularly those with open wounds. The development of any new areas of skin damage should prompt review of the method and intensity of preventive measures. The use of these measures to prevent the development of pressure-induced injury is reviewed separately.

WOUND MANAGEMENT

Treatment by stage:

- Debridement — Necrotic tissue promotes bacterial growth and impairs wound healing. Debridement (mechanical, surgical, enzymatic) is a standard component of basic wound management.

- Stage 1 and 2 skin injuries do not have necrotic tissue and therefore will not require debridement. Broken blisters associated with stage 2 injuries may require minor debridement.

- Stage 3 and 4 injuries may require debridement if necrotic tissue is present. A healthy granulating stage 3 or 4 wound does not require debridement.

- An unstageable injury or an area of suspected deep tissue injury will require debridement to remove necrotic tissue (slough or eschar) that is preventing the determination of injury depth.

Surgical debridement is often necessary to remove areas of extensive tissue necrosis or thick eschar.If sharp debridement of a heel eschar becomes necessary, it should be undertaken carefully by an experienced wound care clinician.Debridement should be discontinued once necrotic tissue has been removed and granulation tissue is present.

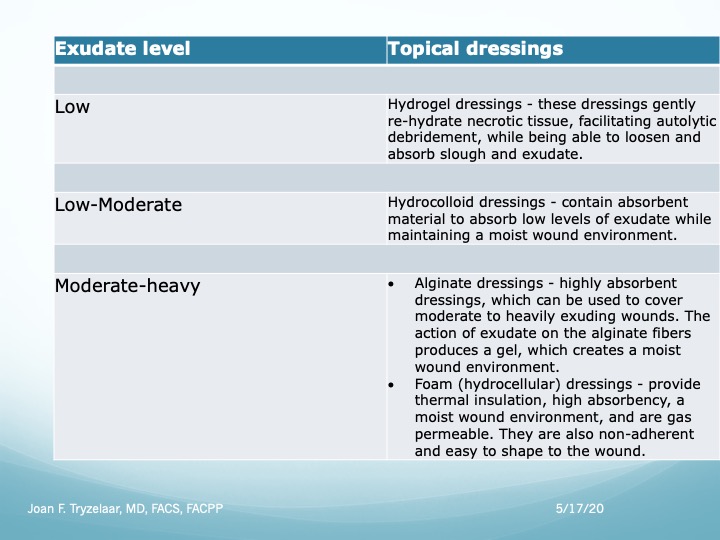

Wound dressings

- Choices for a dry wound include saline-moistened gauze, transparent films, hydrocolloids, and hydrogels.

Adjunctive therapies — A variety of adjunctive therapies such as electrical stimulation, negative pressure wound therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, hyperbaric oxygen, topical oxygen, and application of growth factors to the wound have been investigated for the treatment of pressure-induced skin and soft tissue injuries, but the indications for their use remain uncertain. Some of these adjunctive therapies are discussed below. - Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) enhances wound healing by increasing blood flow, decreasing edema, and increasing the formation of granulation tissue

- Many topical agents have been investigated, including medicinal honey, and alginates with or without added antibacterial Ag.

MONITORING

More than 70 percent of patients with stage 2 pressure injuries, 50 percent with stage 3 pressure injuries, and 30 percent with stage 4 pressure injuries were ulcer free at six months with standard wound care. Among those followed over two years, 77 percent of stage 4 pressure injuries had healed.

The following parameters of care should be monitored daily and documented:

- Evaluation of the ulcer

- Status of the dressing, if present

- Status of the area surrounding the ulcer

- Presence of pain and adequacy of pain control

- Presence of possible complications, such as infection

WOUND COVERAGE

Most pressure-induced injuries are successfully managed using basic principles of wound care and dressings. Direct wound closure is usually not possible; thus, wound coverage entails using a skin graft, skin flap, or myo-cutaneous flap, often as a staged procedure. Prior to graft or flap placement, the wound should be free of devitalized tissue and infection, and patient factors predisposing to development of pressure-induced injuries should be corrected, where possible. Nutrition should be optimized, and smokers should be encouraged to stop since continued smoking impairs wound healing and may result in higher rates of recurrence. Colostomy, which diverts the stool, is another option if the site is prone to fecal contamination.

TREATMENT

Treating pressure injuries involves reducing pressure on the affected skin, caring for wounds, controlling pain, preventing infection and maintaining good nutrition and frequently require many different care team members:

- A primary care physician who oversees the treatment plan

- A physician or nurse wound care specialist

- Nurses or medical assistants who provide both care and education for managing wounds

- A social worker who helps you or your family access resources and who addresses emotional concerns related to long-term recovery

- A physical therapist who helps with improving mobility

- An occupational therapist who helps to ensure appropriate seating surfaces

- A dietitian who monitors your nutritional needs and recommends a good diet

- A doctor who specializes in conditions of the skin (dermatologist)

- A neurosurgeon, vascular surgeon, orthopedic surgeon or plastic surgeon

Successful medical management of pressure injuries relies on the following key principles:

- Reduction of pressure

- Adequate débridement of necrotic and devitalized tissue

- Control of infection

- Meticulous wound care

Assess and Treat the Wound

Local Wound Care

Assess and Treat the patient

Treat the cause. In pressure injuries that means reducing or eliminating the pressure, friction or shear.

Strategies include:

- Repositioning: regular and frequent turning and repositioning using pillow and wedges to reduce pressure on bony prominences

- Using support surfaces.

MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

Mortality risks of non-healing pressure-induced injuries are approximately two to three times more likely to die compared to other patients.

However, affected patients tend to have many other co-morbid conditions. After adjusting for co-morbidities, the presence of a pressure-induced injury is at best a weak predictor of mortality, as expressed by these NPIAP 2017 Position Statements:

- Position Statement 1: The diagnosis of a “pressure injury” does not mean that the health care provider(s) “caused” the injury.

- Position Statement 2: Some pressure injuries are unavoidable despite provision of evidence based care by the health care team. The NPUAP has long maintained that some pressure injuries are unavoidable and has held two consensus conferences in an effort to clarify this issue.3,4 As a result, in any legal matter, “causation” should not be implied by use of the word “injury”.