A dramatic increase in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coupled with a similar decrease in coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has characterized the treatment of coronary artery disease for the 20 years.

The just released FREEDOM trial results[1] have once again confirmed that diabetic patients with coronary artery disease have better outcomes with CABG than with PCI – even if contemporaneous techniques are used.

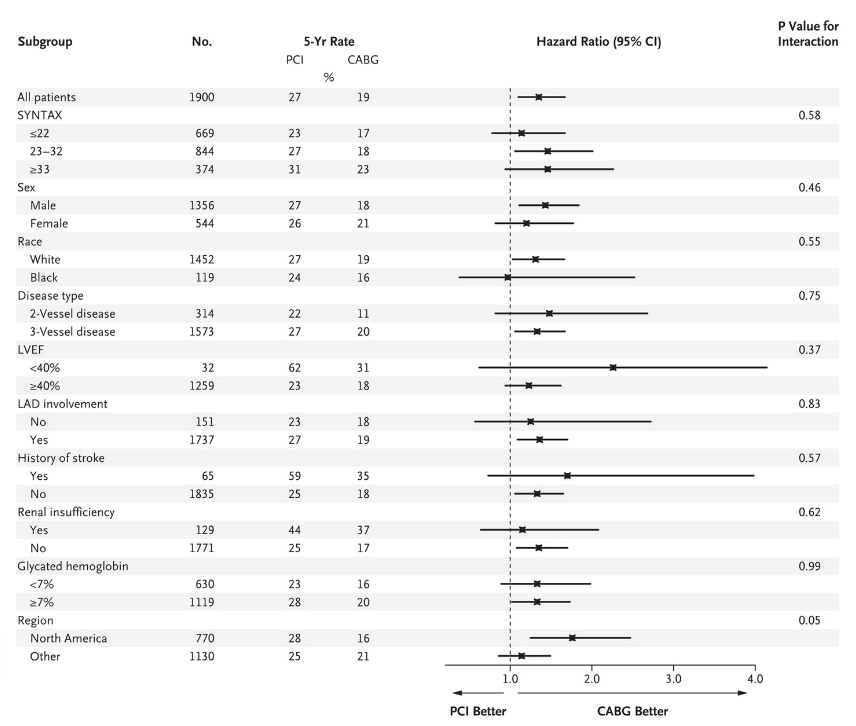

Significant this time is the superiority of CABG for all risk factors examined, not just in patients with depressed LV function and 3-vessel CAD, but even more significantly, in patients even with a low SYNTAX score and also 2-vessel CAD:

This should not be a surprise; since the mid-nineties many previous studies, including one that I co-authored in 2001.[2], have demonstrated the same. After publication of the original BARI trial [3] in 1997 the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued a clinical alert [4] that CABG had better rates of survival than PCI in patients with diabetes.

This should not be a surprise; since the mid-nineties many previous studies, including one that I co-authored in 2001.[2], have demonstrated the same. After publication of the original BARI trial [3] in 1997 the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) issued a clinical alert [4] that CABG had better rates of survival than PCI in patients with diabetes.

The NHLBI recommendations have been largely ignored by cardiologists ever since, as have the results of at least 10 other studies that confirmed the original BARI results.

In an editorial that accompanied the article, the author discussed two possible explanations for the increasing numbers of diabetics treated with PCI despite evidence to the contrary:

- Earlier studies were ignored because of outdated techniques;

- The same physician who does the diagnostic coronary angiography, recommends the treatment, and performs the PCI immediately. An informed discussion about alternative treatment options, either medical therapy or CABG does not take place.

What was not discussed is this:

- The increase in PCI in this high-risk sub group suggests a specific practice of “target lesion” revascularization rather than an emphasis on complete revascularization, not influenced by across the board recommendations from the various medical associations;

- It also suggests long term considerations play little or no role and that device manufacturers and economic benefit may have a much larger influence on treatment for CAD than simply doing what is best for the patient;

- “Percutaneous coronary intervention (stenting)… cost(s) billions of dollars and (has supported) the existence of (an) entire specialty for many years.” [5]

A surprise in this study was the higher stroke rate of 1.8% after CABG than what has been reported elsewhere. A study published in JAMA in 2011 of 45432 patients who underwent CABG surgery at the Cleveland Clinic showed a declining stroke rate from 2.69% to 0.91%, even as even disease severity continued to rise during the period 1988 to 2010:

| CABG technique | Intraoperative stroke rate, % (n) | Postoperative stroke rate, % (n) | Overall stroke rate, % (n) |

| Beating heart, on-pump (n=234) | 0 (0) | 1.3 (3) | 1.7 (4) |

| Beating heart, off-pump (n=2163) | 0.14 (3) | 0.6 (13) | 0.79 (17) |

| Arrested heart, on-pump (n=18 970) | 0.50 (95) | 0.80 (152) | 1.3 (253) |

These results are similar to a metanalysis of 19 trials, in which 10,944 patients were randomized to CABG versus PCI. The 30-day rate of stroke was 1.20% after CABG compared with 0.34% after PCI (odds ratio: 2.94, 95% confidence interval: 1.69 to 5.09, p < 0.0001). [6]

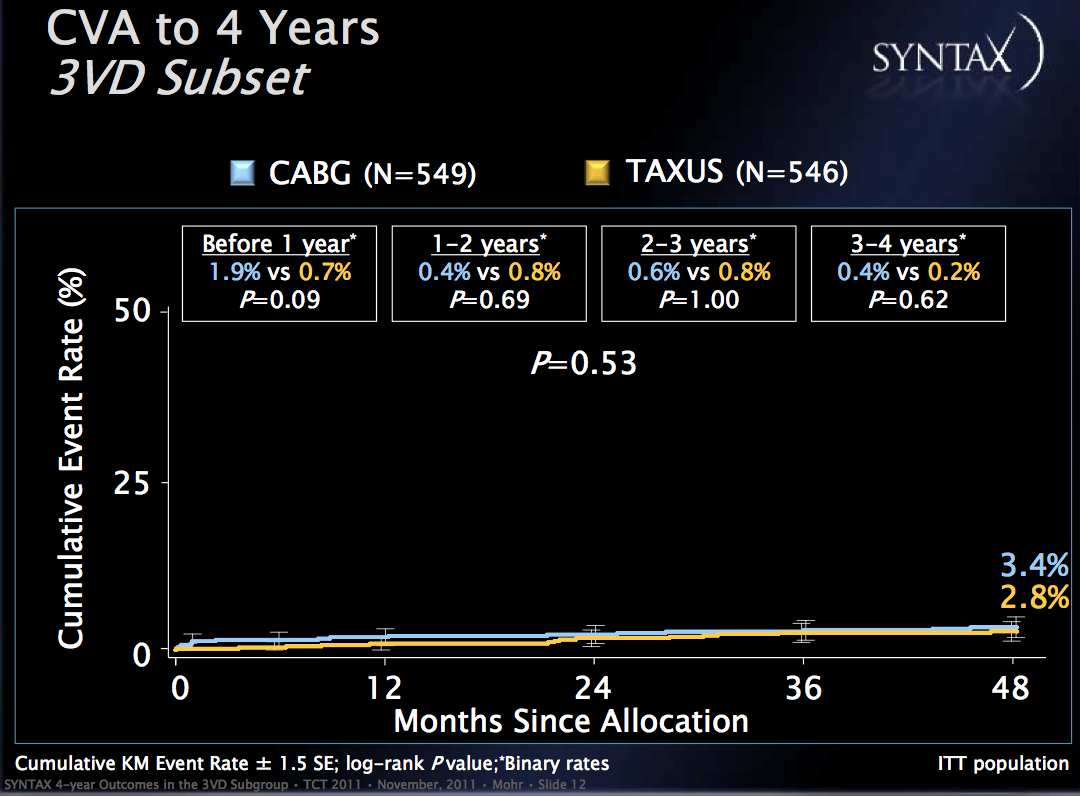

In FREEDOM the stroke rate from 2-5 years rose to 2.8-5.2%, vs. 1.5-2.4% for PCI. Why a higher stroke rate in CABG patients occurred is unclear, as the effect of surgery ceases to be an issue after the immediate peri-operative period. While the majority of strokes (87%) were ischemic, there is no mention in the study of the presence and/or progression of carotid artery disease, or of repeat procedures that might account for embolic strokes after the initial procedure. In comparison,the SYNTAX follow-up results only showed a difference in stroke rate in patients with three vessel disease during year one:

References:

[1] Farkouh, ME et al “Strategies for mulitvessel revascularization in patients with diabetes” NEJM 2012; DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211585.

[2] Survival of patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease after surgical or percutaneous coronary revascularization: results of a large regional prospective study. Niles NW et al. of the Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group, J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37: 1008–1015

[3] The Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) Investigators. Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with angioplasty in patients with multivessel disease. N Engl J Med 1996;335:217-25.

[4] National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Clinical alert: bypass over angioplasty for patients with diabetes. US National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, September 21, 1995

[5] Reversals of Established Medical Practices: Evidence to Abandon Ship. Vinay Prasad, MD et al, JAMA. 2012; 307(1):37-38

[6] Risk of Stroke With Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Compared With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Tullio Palmerini, MD et all, J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(9):798-805.

Comments 1

Pingback: Cost-Effectiveness of PCI with Drug Eluting Stents versus CABG - Cardiac Health