Sudden death in young athletes is a rare but tragic event. Most of these sudden deaths are due to underlying and undiagnosed cardiac conditions. And most of the heart conditions that cause sudden death in young people could have been diagnosed with careful testing. So, it seems to make sense to carefully screen all young athletes for heart problems before allowing them to participate in sports.

In 490 BC, Phidippides, a young Greek messenger, ran 26.2 miles from Marathon to Athens delivering the news of the Greek victory over the Persians, and then he collapsed and died. This is probably the first recorded incident of sudden death of an athlete.

The possibility that young, well-trained athletes at the high school, college, or professional level could die suddenly seems incomprehensible. It is a dramatic and tragic event that devastates families and the community. Sports, per se, are not a cause of enhanced mortality, but they can trigger sudden death in athletes with heart or blood vessel abnormalities by predisposing them to life-threatening heart irregularities.

Sudden death most commonly occurs in football or basketball, accounting for two-thirds of sudden death of athletes in the US. In the rest of the world, soccer is the sport most commonly associated with sudden death. Sudden death occurs in 1 to 2 in 200,000 athletes annually and predominately strikes male athletes.

Cardiac Risks Associated With Marathon Running

Competitive sports are associated with an increase in the risk of sudden cardiovascular death (SCD) in susceptible adolescents and young adults with underlying cardiovascular disorders. In middle-age/older individuals, physical activity can be regarded as a ‘two-edged sword’: vigorous exertion increases the incidence of acute coronary events in those who did not exercise regularly, whereas habitual physical activity reduces the overall risk of myocardial infarction and SCD.

Marathon running is associated with a transient and very low risk of SCD. This risk appears to be even lower in women and is independent of marathon experience or the presence of previously reported symptoms. Most deaths are due to underlying coronary artery disease.

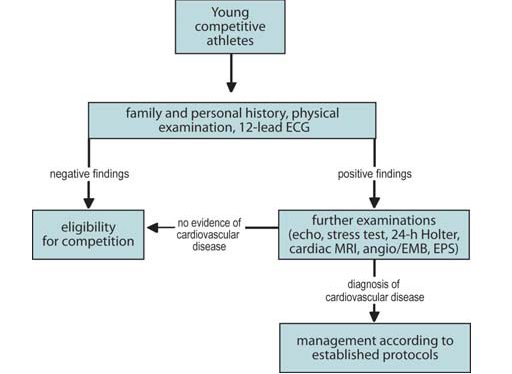

The primary purpose of pre-participation screening is to identify athletes affected by unsuspected cardiovascular diseases and to prevent SCD during sports by appropriate interventions. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) states that the ultimate goal of athletic screening is the detection of silent cardiovascular abnormalities that can lead to SCD. The overall prevalence of cardiovascular diseases that predispose to SCD in young athletes has been estimated to range from 0.2 to 0.7%.

Cardiac diseases detectable by EKG include:

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Myocarditis

- Long QT syndrome

- Brugada syndrome

- Lenegre disease

- Short QT syndrome

- Preexcitation syndrome (WPW)

- Coronary artery diseases

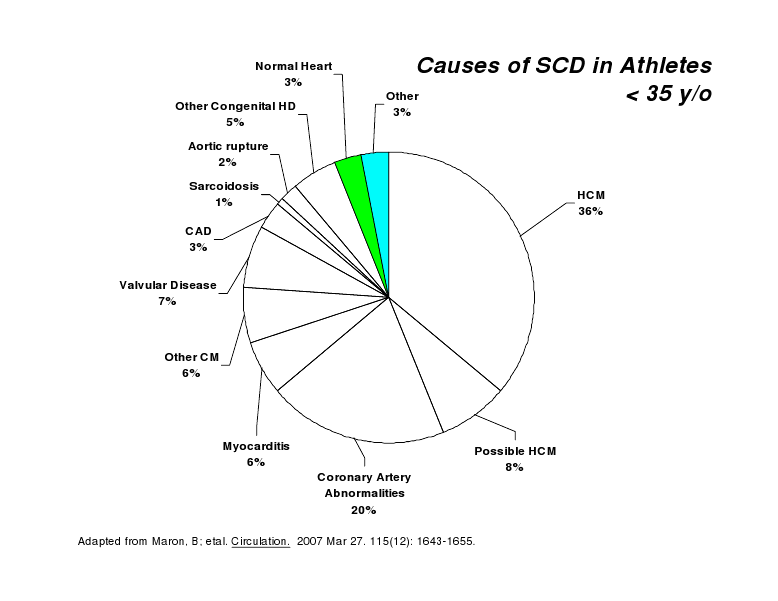

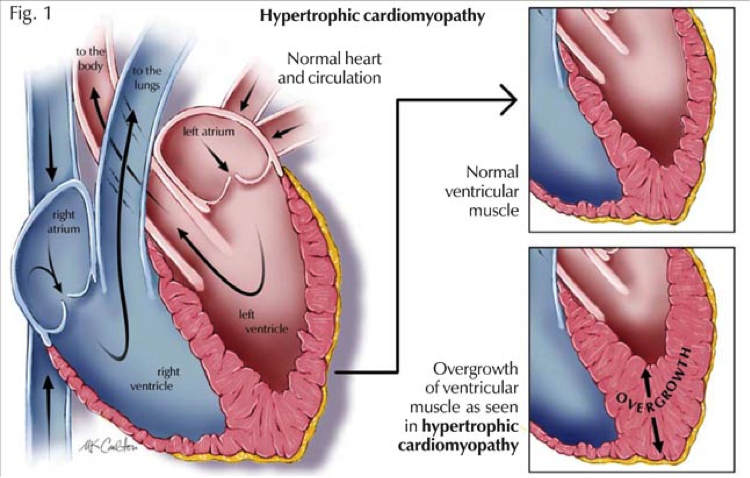

The most common causes of sudden death are congenital abnormalities of the heart and blood vessels, or those that are present at birth. These abnormalities usually produce no symptoms and are disproportionately prevalent in African-American athletes. The most common cause of sudden death is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (Fig. 1), an excessive thickening of the heart muscle that can lead to an irregular heart rhythm called ventricular fibrillation. During ventricular fibrillation, numerous chaotic electrical discharges to the chambers of the heart (400+ per minute) result in no blood being pumped:

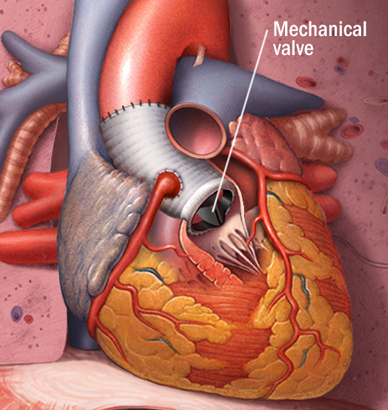

The second most common cause of sudden death in athletes is abnormal coronary arteries (the blood vessels that supply oxygen to the heart muscle). Often, coronary arteries originate from an abnormal location or have an acute twisting angle that slows the blood flow. Other cardiac abnormalities that can cause sudden death are heart valve abnormalities, electrical conduction abnormalities of the heart, and rupture of the aorta (the large blood vessel that carries the blood from the heart to the body).

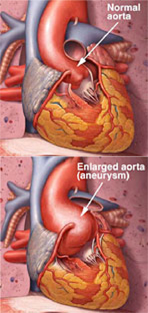

Another cause of sudden death among athletes is Marfan syndrome (Fig. 2).

Marfan syndrome is a heritable condition that affects the connective tissue. The primary purpose of connective tissue is to hold the body together and provide a framework for growth and development. In Marfan syndrome, the connective tissue is defective and does not act as it should. Because connective tissue is found throughout the body, Marfan syndrome can affect many body systems, including the skeleton, eyes, heart and blood vessels, nervous system, skin, and lungs.Marfan syndrome affects men, women, and children, and has been found among people of all races and ethnic backgrounds. It is estimated that at least 1 in 5,000 people in the United States have the disorder.

People who have this medical condition are usually tall, slender, and loose-jointed. It is a hereditary disorder of the connective tissue, which is the basic substance that holds blood vessels, heart valves, and other structures together. Treatment of Marfan syndrome depends on the organ systems affected and could include surgery, medication, lifestyle changes or a combination of these.

Most sudden death in athletes over the age of 30 is due to a heart attack, or blockage of the coronary arteries. The otherwise normal arteries are occluded with lipid plaque. Athletes who are older than 30 are at increased risk for heart attack if they smoke, have high blood pressure, diabetes, elevated abnormal lipids, or a strong family history of heart disease.

Noncardiac causes

A blow to the chest in the area of the heart, called commotio cordis, or cardiac concussion is the most common cause of sudden death in athletes who have no heart abnormality. This condition often occurs in children or adolescents with a nonpenetrating-and usually innocent appearing-blow to the middle of the chest, such as when a baseball, hockey puck, lacrosse ball, softball, or karate blow strikes the athlete’s chest.

Screening

High school and college athletes usually have a physical examination by a physician before participating in organized sports. Athletes with a family history of sudden death, Marfan syndrome, or heart disease at a young age, a history of exercise-induced syncope (fainting), a loud heart murmur, or previous heart surgery require further evaluation by a cardiologist. The preparticipation sports history and physical examination is often not sensitive enough to pick up rare heart conditions. Screening probably does identify 3% to 15% of athletes at risk.

Signs and symptoms

Chest pain, syncope (fainting), dizziness, palpitations (sensation of a rapid or irregular heart beat), fatigue, and excessive or prolonged shortness of breath can be innocent sensations that can accompany intense exercise. Nevertheless, they should be evaluated by a physician because they could be a sign of a heart or lung disorder.

Although sudden death in athletes is devastating, it is very rare and the benefits of exercise for all ages are recognized by improved lipid levels, glucose (sugar) tolerance, enhanced self-assurance, and improved overall quality of life. There are many things we can do to help prevent exertional related illness or death. Exercise in the morning or evening during warm months, drink plenty of fluids, and avoid alcohol and caffeinated beverages. Be sure to inform your physician if there is a family history of heart disease, stroke, or sudden death. If you are over 30 years of age and are starting an exercise program, seek advice from your primary care physician. Don’t smoke, avoid anabolic steroids and stimulants, and report any chest pain, fainting, dizziness, unusually rapid heartbeat, fatigue, and excessive or prolonged shortness of breath to your health care provider.

Surgery

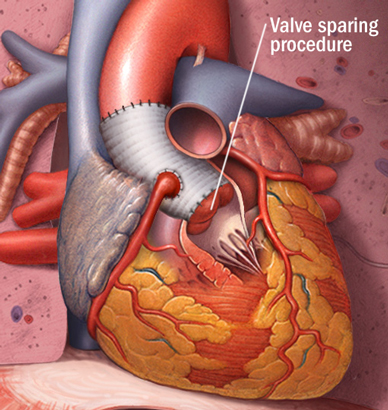

Some patients with Marfan syndrome need heart surgery, including .aortic aneurysm repair, aortic valve repair, aortic valve replacement and mitral valve repair or replacement.

Current Recommendations

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that all high school and college athletes have a screening medical history and physical examination. The medical history should specifically bring to light any of the following symptoms:

- chest pain or discomfort during exercise

- loss of consciousness

- shortness of breath on exertion

- a history of a heart murmur or hypertension

Your child’s doctor should ask about family history, and questions should concentrate on premature (before age 50) death or disability from heart disease in close family members, and whether there is a family history of genetic-related heart problems such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, long-QT syndrome, serious cardiac arrhythmias, or Marfan syndrome.

Evaluation of young athletes:

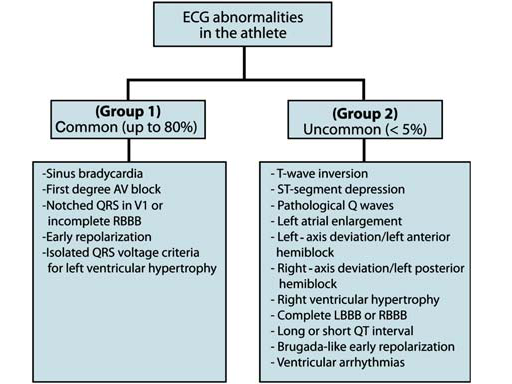

Screening of athletes with abnormal EKGs:

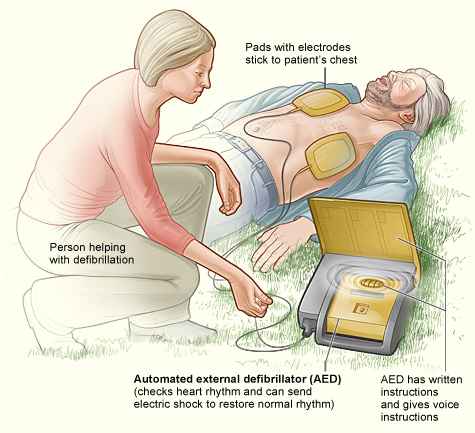

Sudden cardiac death can be treated and reversed, but emergency action must take place almost immediately. Survival can be as high as 90 percent if treatment is initiated within the first minutes after SCD. The rate decreases by about 10 percent each minute longer. Those who survive have a good long-term outlook.

If someone experiences sudden cardiac arrest:

- Call 9-1-1 or 9-9-9/1-1-2 depending on the country (US, UK) should be dialed immediately

- Begin to perform CPR . If performed properly, CPR can help save a life, as the procedure keeps blood and oxygen circulating through the body until emergency medical help arrives.

- Early defibrillation. If a public access defibrillator — also called an AED (Ambulatory External Defibrillator) — is available, defibrillate. In adults, sudden cardiac death is usually related to ventricular fibrillation. Quick defibrillation (delivery of an electrical shock) is necessary to return the heart rhythm to a normal heartbeat. The shorter the time until defibrillation, the greater the chance the patient will survive. It is CPR plus defibrillation that rescues the person.

- Once emergency personnel arrive, more traditional defibrillation and initiation of medications can be provided. This type of defibrillation is done through an electric shock given to the heart through paddles placed on the chest.

- Advanced Care. After successful defibrillation, most patients require hospital care to treat and prevent future cardiac problems.

More about AEDs

Automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) are defibrillators with computers that are able to recognize ventricular fibrillation (VF), advise the operator that a shock is needed, and deliver the shock. AEDs are designed to be used by a wide range of personnel such as fire department personnel, police officers, lifeguards, flight attendants, security guards, teachers, and even family members of high-risk persons. The goal is to provide access defibrillation when needed as quickly as possible. CPR along with AEDs can dramatically increase survival rates for sudden cardiac death.

To learn CPR

Learning CPR is the largest gift you can give your family and friends. CPR is easy for most adults and teens to learn. It is a technique designed to temporarily circulate oxygenated blood through the body of a person whose heart has stopped. It involves:

- Assessing the airway

- Breathing for the person

- Determining if the person is pulseless and applying pressure to the chest to circulate blood

The A-B-Cs of CPR:

A – airway

B – breathing

C – circulation

(chest compressions)

To learn more about CPR: call the national American Heart Association at 1-800-AHA-USA1, or go to the American Heart Association Web site at http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/CPRAndECC/CPR_UCM_001118_SubHomePage.jsp

(From: Risk of sports: do we need a pre-participation screening for competitive and leisure athletes? Domenico Corrado et al, Eur Heart J. 2011 Jan 29)

References:

- Maron BJ. Sudden Death in Young Athletes. N Engl J Med. 2003:1064-1075.

- Maron BJ, Chaitman BE, Ackerman MJ, et al. Recommendations for Physical Activity and Recreational Sports Participation for Young Patients with Genetic Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2004;109:2807-2816.

- Maron, BJ, Thompson, PD, Ackerman, MJ, et al. Recommendations and considerations related to preparticipation screening for cardiovascular abnormalities in competitive athletes: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2007; 115:1643.

- Marfan Syndrome; Treatment: http://www.mayoclinic.org/marfan-syndrome/treatment.html