As is well known, although restriction of diet often results in initial weight loss, more than 80 per cent of obese dieters fail to maintain their reduced weight.

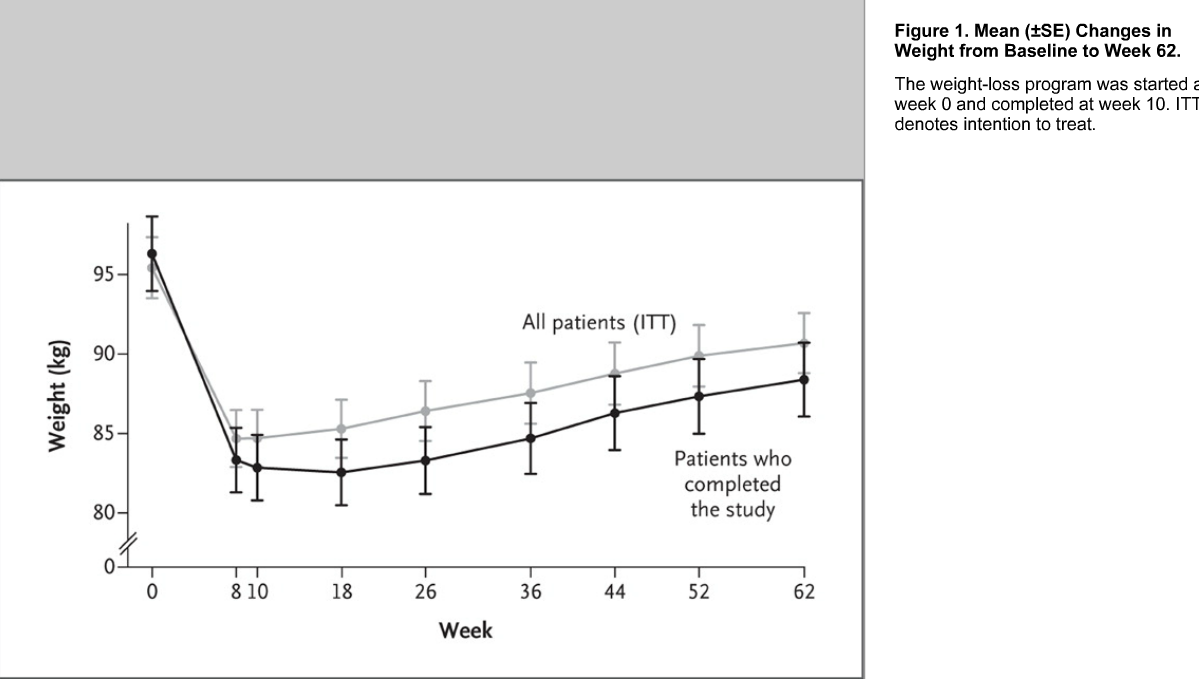

A new study from Australia involved 50 overweight or obese patients without diabetes in a 10-week weight-loss program using a very-low-energy diet. Levels of appetite-regulating hormones were measured at baseline, at the end of the program and one year after initial weight loss.

Results showed that following initial weight loss of about 13 kgs, the levels of hormones that influence a sensation of hunger changed significantly. Weight loss led to significant changes:

| Decrease | Increase |

|---|---|

| Leptin | Ghrelin |

| Peptide | Gastric inhibitory polypeptide |

| Cholecystokinin | Pancreatic polypeptide |

| Insulin | A significant increase in subjective appetite |

At the end of week 10, participants received individual counseling and written advice from a dietician and were also encouraged to engage in 30 minutes of moderately intense physical activity on most days of the week. Participants regained around 5kgs during the one-year period of study.

There are more than 1.5 billion overweight adults, including 400 million world-wide. A new study, published in NEJM, suggests that diet and exercise alone is not particularly effective in the treatment of obesity. The study showed that obese dieters regained much of their original weight after one year. The authors concluded that although dietary restriction often results in initial weight loss, the majority of dieters failed to maintain their reduced weight, perhaps because of hormones involved in the regulation of body weight, and not simply be the result of the voluntary resumption of old habits.

(Among other things, body weight is regulated by hormones released from the GI tract, pancreas, and fat tissue integrated, primarily in the hypothalamus. Hormones that regulate food intake and energy expenditure include leptin and insulin).

This paper has prompted a review of the recent obesity literature as well as the new dietary guidelines. While undoubtedly true for some patients, after my discussion in the gym I have several observations:

- Diet was the only means of weight reduction. Participants were only adviced afterwards to start with a modest exercise program.

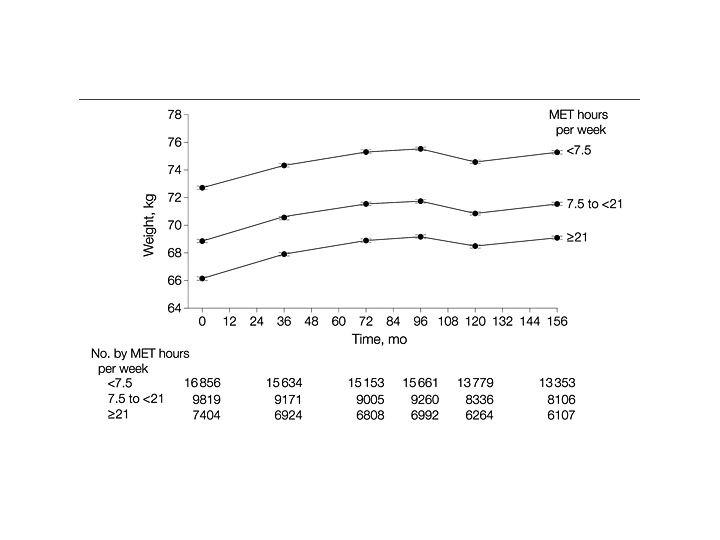

- An obvious conclusion would be that diet alone is not good enough, it requires hard work. Supporting the outcomes noted in this paper, another study followed 34000 US women in their fifties from 1992-2007, the difference being a focus on exercise. The results suggested it is necessary to exercise hard (21 MET hours/week, equivalent to 60 minutes, or about 600 Calories/day of moderate – intensity activity per session), impossible with occasional 30 minute mild work-outs:

- Even so, only those with a BMI <25 were successful in maintaining their weight by gaining less than 2.3 kg throughout the study period. Note how alike the graphs look:

These and other studies would suggest the following:

- Would a strenuous diet following the new 2010 dietary guidelines combined with vigorous, sustained exercise make a difference, or is obesity just a “hormonal imbalance”?

- It is hard to believe that today’s “obesity epidemic” is only the result of factors we cannot control. How does that account for the much more normal weights of only a few generations ago?

- Are these factors, once activated by obesity, impossible to turn of?

The new dietary guidelines and Michelle Obama’s sponsorship of childhood obesity, helped perhaps by subsidizing healthful food options, may be a start.

Ref:

1) Long-Term Persistence of Hormonal Adaptations to Weight Loss. Priya Sumithran, M.B., B.S., et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1597-1604

2) Physical Activity and Weight Gain Prevention, I-Min Lee, MBBS, ScD et al. JAMA. 2010;303(12):1173-1179.